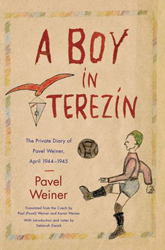

As I mentioned in my earlier post about the young diarist Helga Pollak, there were many  people who kept diaries in Terezin, including children. Many of these documents have been lost, which makes the ones we do have all the more valuable. One diary that has been translated and published in English belonged to a young boy named Pavel Weiner.

people who kept diaries in Terezin, including children. Many of these documents have been lost, which makes the ones we do have all the more valuable. One diary that has been translated and published in English belonged to a young boy named Pavel Weiner.

Pavel was born and raised in Prague and lived in a middle-class home with his parents Ludvik and Valy and his older brother Handa. The family was not particularly religious, but their social network consisted mainly of their Jewish friends and relatives. Everything changed when the Nazis came to power and began enforcing anti-Jewish laws. And then in May 1942, Pavel and his family was sent to Terezin, ending the life they had known. The family was separated and assigned to different barracks, and Pavel was sent to Room 7 in building L417, which was the designated Kinderheim (children’s home) for Czech boys. The Kinderheim was created by Jewish administrators of Terezin and was designed to create better living conditions for the children and to facilitate secret classes for them.

Much of Pavel’s diary takes place in the heim, and focuses on his relationships with the other boys and the youth leaders who ran his heim. He didn’t start writing his diary until April 1944, when he was twelve years old. Despite the situation he was in, many of the challenges Pavel faced were interpersonal. He argued with the boys, and was sometimes teased and excluded by them. This led to Pavel feeling alienated from them much of the time. He longed for affirmation from Franta, his youth leader, and often was hurt when Franta appeared to favor other boys over him. Pavel worried intensely about his father’s health and his mother’s well-being, and yet he often argued with them, in particular with his mother. Pavel also founded a literary magazine, Nesar, which was no easy task, as he struggled to recruit the other boys in his heim to contribute articles and drawings and worked hard to build a readership. Still, he managed to produce thirteen issues, and later contributed to another magazine called Rim Rim.

Many months later, in August 1944, Pavel reflected more deeply on his feelings and the situation he was in. He discussed his anger that two years of his life were stolen from him, that he had no opportunity and no freedom in Terezin. He vowed to write about his feelings so that he might learn from them, to study hard and to start a new life for himself, even within the ghetto walls. He tried hard to keep to his goals, though it was far from easy.

Then in late September 1944, the terrifying news arrived that another transport was scheduled, consisting of men aged sixteen to fifty-five. In a panic, Pavel raced to find his father and learned that his father and his brother Handa were on the transport. Terribly upset and anxious, Pavel returned to his barrack to find that his youth leader, Franta was also on the transport. The sight of Franta sitting around the table with the boys overwhelmed Pavel, and he couldn’t hold back his tears any longer.

In entries that follow, Pavel reflected on the sorrow he felt following the transport and continuously worried about his father and Handa. Most of the boys in his heim were gone, including the few he considered friends and he was terribly lonely, longing for a friend to confide in. He wrote about his loss of enthusiasm and motivation for everything, and no longer felt any comfort or pleasure in anything. Despite his depression and intense feelings of loss, Pavel continued with his studies, continued to write, and began to work in the ghetto bakery and warehouses. Rumors of the Allied advance drifted into Terezin as the winter dragged on, but the liberation still did not come. More and more, Pavel wondered if the liberation would ever arrive and if he would live to see it.