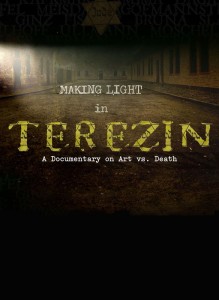

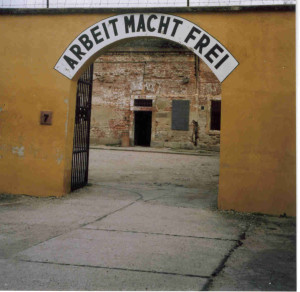

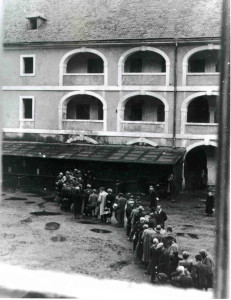

The documentary film Making Light in Terezin, written and directed by Richard Krevolin, gives us deep insight into the ways that theater helped many Jews cope with the terrible reality of their everyday lives in Terezin. Despite the starvation, disease and constant fear of transports, there were musicians and playwrights who continued to produce and perform plays and musical productions, even in the early period of Terezin when such creative efforts were forbidden.

One such work was a cabaret written by two Jewish prisoners of Terezin, which is the focus of the documentary. This cabaret was performed in Terezin but was nearly forgotten after the war. Through the efforts of a highly talented group of individuals, this cabaret was rediscovered, translated and performed in Terezin in 2012 for an audience which included Terezin survivors.

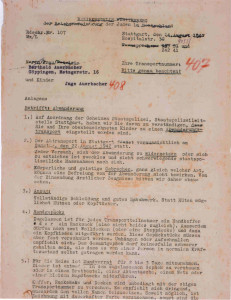

Dr. Lisa Peschel, a lecturer in Theater at the University of York, learned of the script while she was in the Czech Republic conducting research for her dissertation. In 2004, she attended a meeting of Terezin survivors and asked if anyone had documents from the camp. Two sisters spoke with Dr. Peschel and one of them mentioned that she danced in Terezin and had a script of a cabaret.

When Dr. Peschel met with the women and reviewed the script, she realized that she had never seen it before, that it was a one of a kind work. She translated the script into English and soon came to believe this cabaret needed to be revived, to be performed again. She went to the Playwrights’ Center in Minneapolis, where she connected with Hayley Finn and Kira Obolensky, and the three women collaborated to revive this cabaret. It was an immense task, since some of the humor was lost in translation and the script and musical score were incomplete. Dr. Peschel consulted numerous individuals to help decipher the humor. Some parts of the script needed to be adapted, as did some of the musical scores, all of which were done with the utmost care to remain true to the original script.

Playwright and filmmaker Richard Krevolin first learned of this project from Hayley and Kira when one of his plays was running at the Playwrights’ Center. He was captivated by the story of how creative individuals continued to produce art and music in Terezin. When he learned that Hayley, Kira and their actors were traveling to Terezin to perform this cabaret for survivors, Richard decided to document their performance and visit to Terezin on film. He also conducted extensive research on Terezin and the role of theater in the camp, interviewing survivors and scholars.

One of the survivors, Pavel Stransky, was a co-author of the cabaret script, and at age 90, is the only surviving author. Pavel discusses the role of art in Terezin, stating, “art is mental resistance. Art helps, helps to survive.” He also mentions how the humor in the cabaret allowed the prisoners to laugh, which Pavel believes is essential for survival and is also an act of resistance against regimes that rule by terror.

These themes are explored at length throughout the documentary, and are commented on by other Terezin survivors and other individuals who were involved with this project. This documentary sends a powerful message about how creativity and laughter foster hope, how incredibly resilient the human spirit can be, and how in pursuing their art, the prisoners of Terezin performed a heroic act of resistance against the Nazis. I highly recommend watching the documentary Making Light in Terezin to see the production of the cabaret, to hear the stories of Pavel and other survivors and to learn more of how theater and humor helped many prisoners to cope and endure in Terezin.

References (both available on Amazon)

Making Light in Terezin (DVD)

Making Light in Terezin: The Show Helps Us Go On (accompanying book by Richard Krevolin and Nancy Cohen)