In 1997, a middle-aged Milwaukee man named Burton Strnad was cleaning out his mother’s basement when he made a remarkable discovery. In a dusty, unmarked box he found a large red envelope bearing a Nazi swastika stamp. He felt a chill as he slowly opened the envelope.

Inside he found a letter from his father’s cousin Paul Strnad, a black and white photograph of Paul and his wife, and eight beautifully illustrated dress designs in vibrant watercolors.

The date on the letter was December 11, 1939, and it was addressed to Burton’s father, Alvin. In his letter, Paul explained that he was desperately trying to leave Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia with his wife, who was unnamed in the letter.

And Paul believed that their last chance for escape rested on the talent of his wife, a highly esteemed dressmaker and designer in Prague. Paul sent eight of his wife’s designs to Alvin and asked him to try to find a job for his wife. If his wife could land a job as a designer or seamstress, Paul hoped that they would finally be able to secure visas to the United States.

Burton’s father never mentioned the letter to him, and he didn’t know what had happened to Paul and his wife. Recognizing that he had uncovered a treasure, Burton donated

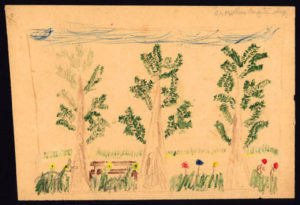

the letter and designs, along with the photo of Paul and his wife to the Jewish Museum Milwaukee. The museum displayed the vibrant drawings sketched by an

unnamed designer, which captivated countless visitors.

The museum staff also launched an ambitious project to uncover the identity of the woman who created these designs. Researchers from the museum scoured the Yad Vashem archives and finally discovered that her name was Hedwig Strnad.

They discovered that despite Alvin’s best efforts, securing visas for Paul and his

wife proved to be impossible.

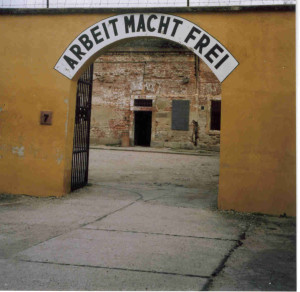

Like so many Czech Jews, the couple was deported to Terezin, and later to the Warsaw Ghetto. It is certain they did not survive the war, and were most likely murdered in either the Warsaw Ghetto or the Treblinka death camp. Other than that, nothing else was known about them.

But during the course of their research, a museum intern managed to connect with one of the couple’s nieces who survived the Holocaust, Brigitte Rohaczek, who recalled a

few precious memories of her aunt. She remembered that her aunt was affectionately known as Hedy, had vibrant red hair, was always beautifully dressed, and enjoyed

smoking cigarettes. Brigitte also recalled that Hedy was kindhearted, always in a good mood, and had a wonderful sense of humor.

As these small details about Hedy emerged, the museum researchers and staff grew even more deeply invested in her story. And when a museum visitor suggested that they actually create Hedy’s designs, the staff decided to take action.

The museum’s executive director, Kathy Bernstein, approached the head of the costume department of the Milwaukee Repertory Theater, who agreed to help bring

Hedy’s innovative and elegant designs to life.

Creating Hedy’s outfits was not a simple task, given that all the theater’s costume shop had to work from were two-dimensional images which gave no indication of the fabrics

or patterns. The costume team conducted meticulous research into the clothing of the time period in order to interpret Hedy’s designs as authentically as possible.

Piece by piece, each article of clothing emerged. A tailored violet coat with matching hat and shoes. A fitted turquoise day dress, a black dress with a pink rose pattern, and an airy, flowing ball gown. And each outfit was paired with custom accessories such as gloves, scarves, and fascinators.

The team ensured that every detail was crafted with the utmost care, and even

created historically accurate labels that said “Hedy original”, which they sewed into

every dress and coat. All together, the process took about 3,000 hours and spanned

over 10 months.

At last, Hedy’s designs were complete, and they were later featured in a traveling exhibit called Stitching History From the Holocaust, which opened at the Jewish Museum Milwaukee in 2014. Since then, the exhibit has traveled to many places throughout the United States, including the National Czech & Slovak Museum & Library (NCSML) in Cedar

Rapids, Iowa and the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Lower Manhattan.

The exhibit serves as a powerful tribute to Hedy Strnad, an incredibly talented designer who tragically never had the chance to bring her vision to life. And Hedy’s story forces us to acknowledge the countless people who died in the Holocaust whose unique talents and gifts the world never saw, whose cherished hopes and dreams were never realized.