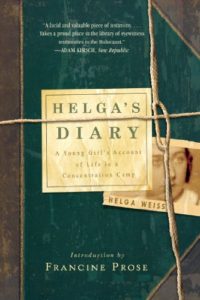

Helga Weiss was a young Terezin artist whose story has become known in the past few years with the publication of her diary. Helga’s diary and paintings give us valuable written and artistic testimony of the Holocaust through the eyes of a young girl. Helga’s paintings are an excellent resource for teaching students the Holocaust.

Here is a guide on how to introduce students to Helga’s world using a selection of her paintings. The paintings can be used before teaching Helga’s diary, or as a more general introduction to the Holocaust.

Selecting the Paintings

Helga created dozens of paintings that you can choose from. I recommend choosing from the selection of her paintings profiled on The Guardian. Here are some of the ones I suggest showing your students:

- List of Possessions, January 1943

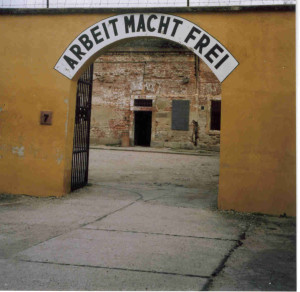

Helga’s parents take an inventory of all their possessions to hand over to the Nazis. - Arrival in Terezin, 1942

A group of Jewish prisoners walks into Terezin with their luggage as a guard watches them closely. - The Dormitory in the Barracks at Terezin, 1942

A scene of the room Helga and her mother shared with 21 other women. - Summons to Join the Transport, 24 February 1942

A girl sits up in her dark bunk as a flashlight shines on her. Helga wrote that the summons to join the transports often happened at night. - For Her 14th Birthday, November 1943

A painting Helga made as a birthday gift for her best friend Francka. Sadly, Francka was murdered in Auschwitz before her 15th birthday.

Observe the Paintings

Show your students Helga’s paintings and tell them it depicts a scene from daily life in the Terezin ghetto during World War II. You can project the image in front of the class, or you could hand out copies of the paintings to your students. A large color image is best so students can see the color of the paints Helga used.

Give your students the chance to take a long look at each painting and to note the details. Encourage them to notice the colors, the shapes, what the people in the painting are doing, and the expressions on their faces. Ask them what they observe, and write down the observations on the classroom whiteboard. At this point, the class should just observe the details, not interpret or analyze anything.

Ask your students what questions they have about the painting. Give them a few minutes to write down as many questions as they can. Once the time is up, divide your class into small groups and instruct them to come up with some answers to their questions.

Analyze the Paintings

Now ask your students to think about the artist herself. How old is she, and why is she painting scenes of life in the Terezin ghetto? What was it like for her to live in the ghetto? Who is her audience, and why is she painting for them? Have the students write down their thoughts and ask for volunteers to share with the class.

After you hear your students’ input, introduce them to Helga Weiss, a twelve-year-old girl from Prague who was sent to Terezin with her parents in 1941. Tell them how she and her mother were separated from her father, and how she decided to send her father a painting to cheer him up. She painted a happy scene of two children building a snowman, but her father surprised her with his reaction. He wrote her a letter telling her “Draw what you see!”.

Ask your students to think about why her father wanted her to record life in the ghetto. Now have them look at the painting again and draw their attention to specific details. Emphasize that each detail is depicting something that the artist Helga actually observed in Terezin. Ask them to put themselves in the scene and to imagine it unfolding around them. How does it make them feel? How do they think Helga would have felt as she drew the scene?

This is one idea for presenting Helga’s paintings to your class in a meaningful way that can help them to feel more invested in her story. A big part of teaching the Holocaust effectively is presenting it in a way that students can engage with, and helping them feel a personal connection with someone who experienced it.