One of the countless remarkable stories of creative life in Terezin concerns a secret

literary magazine called Vedem. Founded in 1942 by 14-year-old Petr Ginz, the magazine documented life in Terezin through the stories, poems, and artwork of the boys who lived in Barrack L417, also known as Home One. But no one outside of Terezin would have known of Vedem if it weren’t for a courageous young boy named Zdenek (Sidney)Taussig.

Sidney Taussig’s Early Life

Sidney Taussig was born and raised in Prague, and as a child was known as Zdenek. His grandparents were observant Jews, though the family lived on the outskirts of Prague, some

distance away from the city’s Jewish community. Because of this, Sidney went to a public school and most of his friends were Christian. Sidney’s early childhood memories were happy ones, and he felt fully accepted by his non-Jewish friends.

Everything changed when the Nazis seized control of Czechoslovakia in 1939 and began to pass anti-Jewish laws. Sidney started experiencing severe discrimination and began to feel very suspicious of non-Jews. Due to these laws, Sidney’s

father lost his contracting business, and Sidney, who dreamed of being an engineer, was forced to leave his gymnasium, a school that prepared students for university.

Then in 1941, Sidney, along with his sister, parents, and

grandparents, was transported to Terezin.

Life in Terezin

Upon arrival at Terezin, Sidney, his parents, and sister were sent to live in a cramped room with nine other people, and all four were assigned jobs in the camp.

Sidney’s mother was a nurse in the infirmary, his father secured a position as a blacksmith, and his sister worked in the fields. Sidney’s uncle trained horses for the SS men, and he found Sidney a job driving horses.

Each morning, Sidney harnessed his horses and went to work harvesting potatoes and other crops. He would drive a wagon through the fields, which women and girls piled high with potatoes, and then delivered them to the ghetto kitchens.

Even though it was against the rules, Sidney regularly smuggled a few potatoes to trade for other food items that he shared with his family, including an occasional piece of meat. He knew the consequences would be fatal if he were caught, but Sidney’s hunger was so great he was willing to take the risk.

Disease and hunger ran rampant in Terezin, and thousands of people died from old age, starvation, and infectious diseases, including Sidney’s grandmother and aunt. As the death toll mounted, Sidney was assigned the horrific task of transporting the bodies of those who died. Other prisoners piled the bodies of the dead onto a wagon, which Sidney drove to the cemetery outside the ghetto walls or to the crematorium.

It’s impossible to fathom the emotional toll this took on Sidney, but incredibly,

he managed to find the inner strength to endure in Terezin.

The Boys of Home One and the Secret Literary Magazine

Sidney drew much of his strength and resilience from his friendships with other boys in Barrack L417, or Home One, where he lived for most of his time in Terezin. The boys formed close bonds with one another, participated in soccer games, and attended secret classes after work.

And together, the boys defied the Nazis by founding a secret magazine called Vedem, where they documented what life in Terezin was really like through their essays, poetry, and drawings. The boys in Home One and their teacher, Valtr Eisinger, guarded their secret closely. They knew if the Nazis ever found out about Vedem, they would all be sent on the next transport east.

Although the boys received great encouragement from their teacher, the driving

force behind the magazine was Petr Ginz, Vedem’s 14-year-old editor-in-chief.

Petr managed to secure an abandoned typewriter which the boys used to type up their work. Soon the ink ran out, and there were no more ribbons, so the boys created the rest of the issues by hand.

Every week the boys would compile their latest writing and drawings into a new issue, which was often around ten pages in length. Then on Friday evenings, they would sit in their bunks and the boys who contributed articles and poems would read their work out loud. Often they’d discuss the articles together, but since the magazine had to remain

a secret, no one outside Home One ever saw it.

They continued to release a new issue every week for nearly two years, and found

that expressing their experiences through art helped them to cope with the grim reality of their situation. On top of this, the shared camaraderie of this experience no doubt strengthened the bond between the boys in Home One.

But tragically, these bonds were frequently broken, as more and more boys were sent away on transports. And in October 1944, Petr was sent to Auschwitz on one of the

last transports from Terezin, where he was murdered in the gas chambers at the age of 16.

The few boys who were left behind stopped writing, and did not release any more issues of the secret magazine. In the end, all of the boys in Home One were sent to Auschwitz, and very few of them returned.

In his testimony, Sidney explained that he owed his life to his father. Sidney was

also assigned to a transport but was spared because his father spoke to Commandant Rahm, the Nazi in charge of Terezin. Sidney’s father managed to set up a review with

Rahm, and during this meeting Sidney said he was the son of a blacksmith and boldly claimed he was a blacksmith, too. In the end, Rahm removed Sidney from the

transport because his father was an excellent blacksmith and his skills were in high demand.

But the transports kept leaving until all the boys were gone – everyone except Sidney. Home One was shut down, and Sidney went to stay with his father.

Before he left L417 for good, Sidney gathered all the issues of Vedem and smuggled them out of the barrack. That night, he tucked the issues into a metal box, which he secretly buried behind the ghetto’s blacksmith shop. Sidney knew he needed to save these issues, because their pages were a record of what really happened in Terezin. They

also memorialized all the incredibly gifted boys of Home One, Sidney’s friends, who were now lost to him forever.

As the end of the war drew near, survivors of Auschwitz and other extermination

camps arrived in Terezin, ragged and starving. Even after three years in Terezin, Sidney was shocked when he saw how emaciated and ill they were. One of Sidney’s jobs was

to transport rotten potato peels by wagon for composting, and the starving prisoners would devour every last potato peel.

By the spring of 1945, Sidney and his father often spotted American planes flying above the camp. They gazed up at the planes and sensed that liberation was near, but didn’t know if they would survive to see it.

Then, in early May, the sound of gunshots rang outside the camp walls, and inside Terezin word spread that the Russian army was nearby. The Germans fled, and soon after, Sidney and another boy were tending to the horses when they heard more shooting. They went to investigate and saw dozens of Russian tanks parked outside the walls.

The Russians liberated Terezin on May 8th, 1945, but the surviving residents were forced to quarantine in the ghetto due to a severe typhoid epidemic. Sidney had access to horses the Germans left behind and his father decided they should leave immediately. That night, they tethered a pair of horses to a wagon, and together with Sidney’s mother, sister, and a few friends, made their escape from Terezin. Before they left, Sidney unearthed the metal box containing the issues of Vedem and loaded it onto the wagon next to their few belongings.

The family traveled by horse and wagon all night, until they arrived back in Prague early the next morning. As they rode through the streets of Prague to their old home,

people recognized them and word spread that the Taussig family had returned. At the age of 16, Sidney was finally home after four years of captivity in Terezin.

Sidney Taussig’s Life After Terezin

When Sidney’s family entered their old home, they found it empty and realized the Nazis had stolen all their possessions. Like so many other Holocaust survivors, they had

to rebuild their lives from nothing.

That fall, Sidney returned to the very same gymnasium he had been forced to leave in 1941. Since he had been able to attend classes in Terezin, he was at the same level as

his classmates, and even outperformed many of them in math and science. After

his graduation, Sidney’s uncle in New York managed to secure U.S. visas for him and his sister.

Sidney was grateful for the opportunity to leave Europe, but he felt torn over what to do with the magazines he’d rescued from Terezin. Since the issues were written in Czech, Sidney felt it was right to leave them in Czechoslovakia. In the end, he brought them to a Jewish orphanage in Prague and gave them to a woman named Mrs. Laup, whose son had also been in Home One.

After Sidney emigrated to America, he lost track of the magazine for many years. He settled in the Yorkville section of Manhattan and focused on building a life for himself, working various odd jobs and attending college classes at night. In his free time, he enjoyed playing soccer and met a young American woman named Marion at one of these games.

They married less than a year later, when Sidney was 23 and Marion was 18.

When the Korean War broke out, Sidney enlisted in the Air Force, where he trained as a radar technician. After the war, he worked as a technician and attended Brooklyn Polytech at night, where he obtained an engineering degree. Over the years, he held engineering jobs in several companies and later went into management at the electronics company General Instruments. With his business success, Sidney and Marion were able to buy a house on Long Island, where they settled with their children Michelle, Ron, and Debra.

Although Sidney regarded Marion as his best friend and had a close relationship with his children, he found it very difficult to talk about his Terezin experiences for many years. He was determined not to burden his children, but as they grew older, they began to ask him about his war experiences. And so Sidney began to speak of the years he spent in Terezin, and found that over time it became easier for him to discuss.

When sharing his experiences, Sidney imparted a powerful lesson to his children. He told them that no matter what hardships they faced in life, they needed to persevere. “You have to be a survivor. You have to survive. If you do the best you possibly can, you’re surviving.”

Years after leaving Prague, Sidney learned that the issues of Vedem were returned to the museum at Terezin for safekeeping, and some were featured in a digital exhibit. Another Terezin survivor, George Brady, had some issues of the magazine translated into English. Many of these translated stories, essays, and poems, as well as many drawings

were published in a book called We are Children Just the Same : Vedem, the Secret Magazine By the Boys of Terezin.

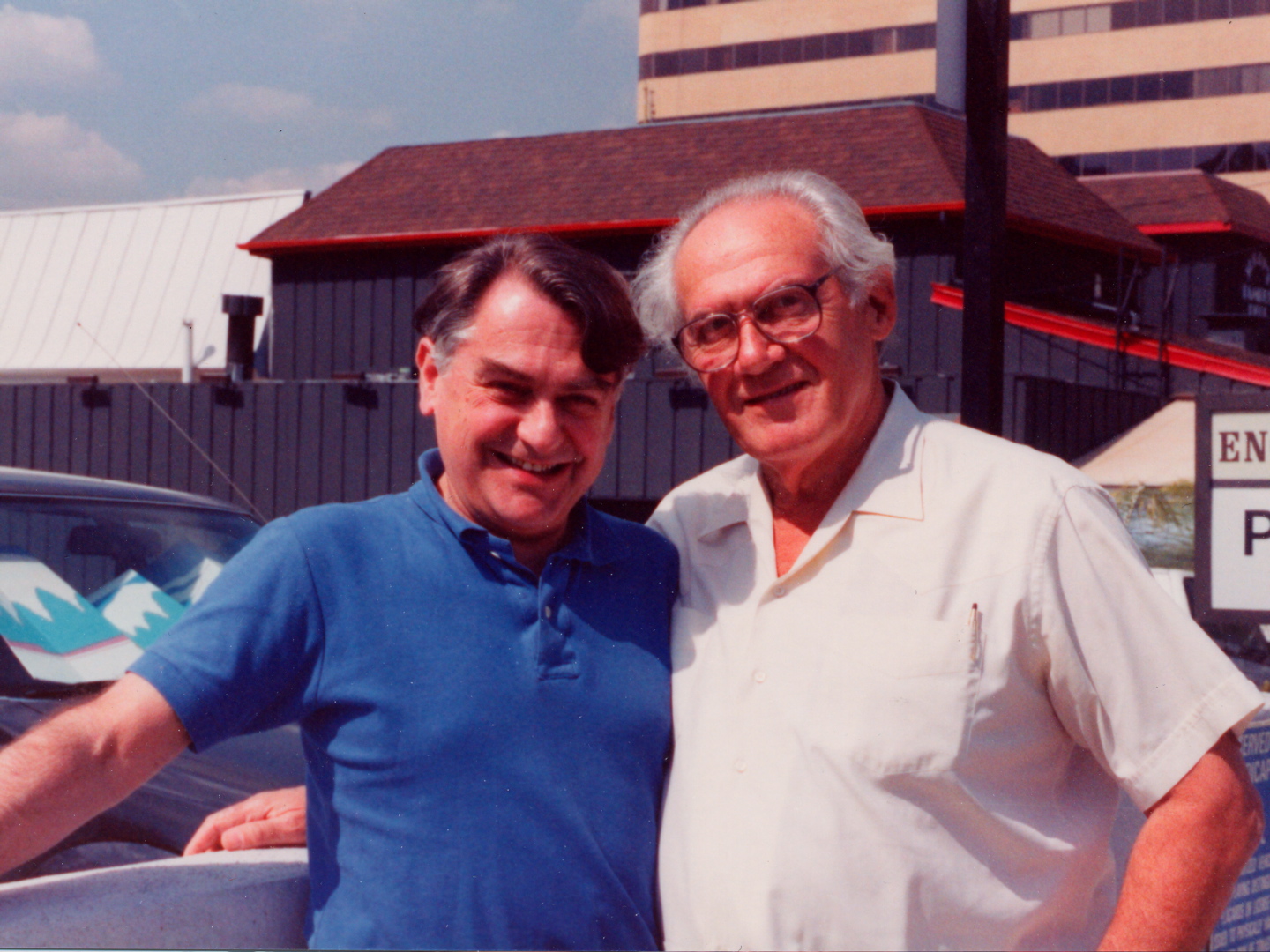

The story of the boys who created Vedem continues to inspire people around the world. In 2019, at the age of 89, Sidney attended a performance by the Keystone State Boychoir that paid tribute to the young writers and artists who contributed to Vedem.

At the age of 91, Sidney recites a poem he wrote as a young boy in Terezin.

And in 2021, The Last Boy in the Second Republic of SHKID, a play based on Sidney’s wartime experience, premiered at the Theatre at St. Clement’s in New York City. Today, Sidney lives in Florida and continues to share the story of the boys of Vedem with younger generations.

Thanks to Sidney’s heroic actions, the legacy of the boys who created Vedem lives on, and serves as a powerful tribute to the human creative spirit that can rise above the most unimaginable circumstances.