One of the many extraordinary individuals dedicated to the children of Terezin was Franta Maier, the madrich or leader of the boys’ home in Room 7 in barrack L417. This was the same home where the young diarist Pavel Weiner was assigned, and he and the other boys who survived remembered the profound impact Franta had on their lives many years later.

Determined, take-charge, passionate, generous and resourceful are some of the words used to describe Franta by those who know him. These traits were already evident when Franta was 18 years old. The year was 1940, and Franta was sent to Prague to complete a teacher training course. There was a severe shortage of teachers to educate the Jewish children who were being expelled from the public schools, so Franta had to complete the course in two months. He passed the state teacher’s exams and was assigned to teach a class of 60 third-graders. Some of the children came from a Jewish orphanage, and Franta noticed that these children were unkempt and anxious, and their lunch consisted only of cold boiled potatoes. Franta spoke with the leader of the Brno Jewish community, Otto Zucker, who listened to his concerns and later observed Franta’s classroom. Nothing changed, however, and in a few months, the Nazis closed the school.

Otto Zucker offered Franta a position as the teaching and education chair at the orphanage, where 200 boys and girls between the ages of 5 and 14 lived. The orphanage was poorly funded because it was dependent on donations. Due to the war, many people were reluctant to provide money. Franta was well-known and popular in the community for being a talented soccer player, and managed to arrange for better washrooms and accommodations.

Franta also managed to introduce many positive changes to the orphanage and organized singing and music groups, Shabbat services and classes. Children from the outside were invited to participate in these activities, and friendships developed. Women from the Jewish community helped with the laundry and taught the children about grooming and how to take care of their clothes. This was a valuable service, because the children at the orphanage regarded themselves as unattractive and inferior to other children.

Franta observed that the children needed someone to listen to them and care about them, someone who could take a leadership role and instill discipline while demonstrating concern. He tried his best to be that person, and encouraged the other orphanage workers to do the same. An especially poignant scene is a description of Franta, a skilled violinist, walking down the hallways when the children were in bed, playing folk songs and lullabies to soothe them to sleep. He did this to comfort them and because he knew this was an experience that these children never had before.

The positive changes that Franta introduced were tragically halted on March 15, 1942, when he and the entire orphanage were transported to Terezin. Franta would need to rely on his intuitive understanding and all he had learned in the past two years to meet the immense obstacles he would face in mentoring the children of Terezin.

Further Reading

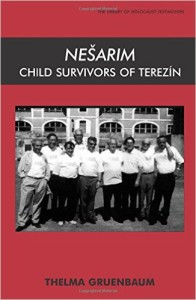

Nesarim: Child Survivors of Terezin by Thelma Gruenbaum