Hana Brady’s story became known to the world through an incredible turn of events. The story involves a battered suitcase with a few words painted on it: Hana Brady, born May 16, 1931, Orphan. Who was the young girl who owned this suitcase? Thanks to the efforts of Fumiko Ishioka, director of the Tokyo Holocaust Education Resource Center, we now have the answer. Here is Hana’s story.

Hana lived with her parents and older brother George in a small Czech town called Nové Město na Moravě. She was described as a happy, active and athletic little girl who was very close to her family. Hana was just eight years old when the Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia. The family’s life became restricted, and they were forced to hand over their radio and other valuables to the Nazis. Their Christian friends stopped playing with them, because their parents feared they would be punished for playing with Jewish children. Hana and George remained close and supported one another during this time.

In March 1941, their mother, Marketa, was assigned to a Nazi transport and taken away. Soon after, they were forced to sew yellow star badges to their clothing along with all the other Czech Jews. When one man in

town refused to comply, a Nazi officer was furious and

ordered the arrests of all the other Jewish men in town. Hana and George’s

father Karel was arrested and taken away a few days later, and the two children

were left with the family’s housekeeper.

Later that day, their uncle Ludvik, a Christian man married to their father’s sister

Hedda, arrived at the house. He had heard the bad news, and came to bring the

children to his home. He helped the children pack, and Hana gathered her

belongings in a large brown suitcase with a polka dot lining.

The children remained with their aunt and uncle until May 1942. That was when

the children received a notice ordering them to report to a deportation center.

They were taken to the center, where they were forced into a large warehouse

with hundreds of other Jewish families. After four days in the warehouse, they were

put on a train and sent to Terezin.

The train stopped at Bohusovic Station, and Hana, George and the others on their transport had to carry their luggage the last few kilometers to Terezin. The children were

separated into homes, and Hana was assigned to the girls’ home in barrack L410. She slept on a thin burlap mattress on a three-level bunk bed and was initially confined to the barrack due to her age.

Hana was unable to see George and missed her brother terribly. Some of the older girls looked out for her, and she became friends with one of them, a dark-haired girl named Ella.

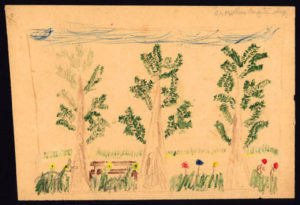

Hana spent her days with the room supervisor and the younger girls, doing chores and attending secret classes in the barrack. They learned songs in music class, the basics of sewing, and art. Hana’s favorite class was art, and she adored her teacher, famous artist Friedl Dicker-Brandeis. Hana produced many drawings, some of which still survive.

After she had been in Terezin for some time, the rules were changed and Hana was finally able to see her brother, who was assigned to the boys’ home in Barrack L417 and was working as a plumber in the camp. The siblings would see each other every chance they could get, and George was determined to do everything possible to take care of his sister. Hana in turn worried about George, and she would set aside her weekly buchta (a sort of plain doughnut) and give it to her brother to eat.

As the months went on, the camp became more and more cramped, and many people died from food shortages and epidemics. And every few weeks, people were assigned to transports heading East,

to some unknown destination.

In September 1944, George was sent away on one of these transports. A month later, Hana was assigned to a transport and was full of hope that she would be reunited with her brother. Hana’s friend Ella helped her to wash her face and hair, because Hana wanted to look nice when she saw her brother again.

The next morning, Hana, Ella and many other girls from their home were put on a dark train, which traveled nonstop for a day and a night. There was no food, no water, no toilet, and no way to know how long the journey was. Hana, Ella and the other girls held hands, whispered stories, imagined they were somewhere else.

On the night of October 23, 1944, they arrived at Auschwitz. The girls were forced out of the car, and ordered to stand on the platform. The guards selected a few of the older girls and sent them to the right.

Hana and the rest of the girls were told to drop their luggage and go to the left, where they were herded into a large warehouse. That night, Hana died in the gas chambers of Auschwitz at the age of thirteen.

George had also been sent to Auschwitz, but he managed to survive the camp, in part due to the plumbing skills he had gained at Terezin. He was liberated in January 1945 at the age of seventeen and returned to the home of his Uncle Ludvik and Aunt Hedda.

He learned that his parents were dead, and for many months searched for news of

his sister. Eventually, he met a teenage girl in Prague who knew Hana from Terezin,

and learned the horrible truth.

In 1951, George moved to Toronto and started a very successful plumbing

business, married and had three sons and a daughter. But despite all his joys

and successes, George’s loss of his parents and beloved sister was never far

from his mind.

Then, years later, in 2000, he received a letter from a woman named Fumiko Ishioka,

the director of a Holocaust Center in Tokyo. She had received a leather suitcase

with polka dot lining at her center – Hana’s suitcase.

Almost nothing was known of Hana, and after months of searching, Fumiko had found George and sent him a letter in the hopes of learning about his sister. Later, George and his daughter Lara traveled to the center in Tokyo to meet Fumiko and a group of schoolchildren known as the Small Wings, and to share Hana’s story.

In March 2004, George and Fumiko learned

that the suitcase was actually a replica created

by the museum at Auschwitz after the original suitcase and many other items from the Holocaust had been destroyed in a fire.

While saddened to hear about the fire, George and Fumiko were grateful that the Auschwitz museum created the replica, which brought them together and allowed them to bring Hana’s story to the world.

Further Reading

Hana’s Suitcase by Karen Levine