In addition to countless artists and creatives, many rabbis and religious leaders were also sent to Terezin. One of these individuals was Regina Jonas, the first woman to be ordained a rabbi. Regina overcame many obstacles to receive her ordination, and dedicated her life to serving Jewish communities in Germany. Even after she was deported to Terezin,

Regina continued to serve, comfort, and inspire those around her. After the war Regina’s story was forgotten for decades, only to be miraculously rediscovered after the collapse of the Berlin wall.

Regina Jonas’s Early Life

Regina was born in Berlin in 1902, and was raised in Scheunenviertel, a poor

Jewish neighborhood. Her parents were Orthodox and ensured that Regina received

a Jewish education. Regina was a gifted and eager student, and by the time she

was in high school, her passion for Jewish studies and Hebrew was evident to her

teachers and fellow classmates.

Impressed by her intellect and intense love of Judaism, Regina’s rabbi

Dr. Max Weil encouraged her to enroll at the liberal Berlin Academy for the Science of Judaism in 1924 to continue her studies. This was one of the few Jewish seminaries

in Germany that admitted women at the time, and most of the female students

intended to become teachers.

But a career as a teacher of Jewish studies wasn’t enough for Regina. She was determined to be ordained as a rabbi, even though most people believed her dream was impossible.

Even though Regina gravitated towards Orthodox Judaism and was not a supporter

of the Reform movement, she chose to attend

a liberal seminary because it was the only one in Germany that might consider ordaining a woman rabbi. At the seminary, Regina gained the support of Dr. Eduard Barneth, who was willing to ordain her.

In 1930, as she neared the end of her studies, Regina wrote a thesis titled: “May a Woman Hold Rabbinic Office?”, in which she drew on her deep knowledge of the Talmud and other Jewish texts to make a compelling case in favor of women rabbis. Regina received praise for her thesis, and earned the respect of her professors.

But tragically, her supporter Dr. Barneth died suddenly and the man who succeeded him refused to let Regina sit for her rabbinate exam.

None of the other professors contested this decision, and Regina ultimately graduated as a religious teacher. For several years, Regina taught Jewish studies at different girls’ schools and by all accounts was an exceptional teacher.

But despite her successes, Regina was determined to achieve her dream of becoming a rabbi.

Ordination and Life as a Rabbi

After five years of tirelessly seeking ordination, Regina’s efforts finally paid off when Rabbi Max Dienemann, the leader of the Conference of Liberal Rabbis, agreed to ordain her. She received her ordination in a private ceremony conducted by Rabbi Dienemann in December 1935, at long last achieving her lifelong dream.

Regina’s ordination was truly groundbreaking, and she made history as the first woman to be ordained a rabbi.

Unsurprisingly, her ordination was highly controversial, and Regina struggled to

gain acceptance as a rabbi. Denied a congregation, she had to find other ways to serve

the Jewish community in Germany. Determined as always, Regina found work as a teacher and hospital chaplain, and was a regular speaker at several liberal congregations in Berlin.

Then, in the late 1930s, the Nazis began arresting rabbis, and Regina faced a

difficult decision. Should she flee Germany, or should she stay behind and

continue to minister to her community?

Though fully aware of the dangers, Regina refused to leave Germany, unwilling to leave her mother behind or abandon her beloved Jewish communities when they needed her the most. She traveled to Jewish congregations across Germany that had lost their rabbis and did everything she could to serve them, even leading special services for people forced to labor in Nazi factories.

Her work with the German Jewish community came to an end in November 1942, when Regina and her elderly mother were sent to the Terezin ghetto.

Regina Jonas: A Rabbi in Terezin

Even in Terezin, Regina continued to live a life of service and dedicated herself

to ministering to the Jewish community.

One of Regina’s fellow inmates was the famous Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl,

who organized the “Department for Mental Hygiene” to provide mental health

services for those imprisoned in Terezin. Regina worked in this department, where

her role was to comfort and assist traumatized new prisoners as they struggled to cope with the terrible conditions of the ghetto. She acknowledged the hardships while

also assuring them that she was there to support them, both psychologically and spiritually.

During her time in the ghetto, Regina also delivered sermons and lectures, in which

she often highlighted influential Jewish women. Many of her sermons encouraged

other Terezin inmates to always strive to find meaning in their lives, in spite of the

terrible circumstances they had to endure.

Given that Viktor Frankl later wrote a famous book on this very subject called Man’s Search for Meaning, it seems likely that Regina’s sermons impacted him as well. Sadly, Frankl never mentioned Regina in any of his writings, so it’s impossible to know for sure.

But some documents Regina herself wrote did survive the war, including a powerful letter in which she described her belief that God called the Jewish people to be a

“blessed nation.” She believed it was her responsibility as a daughter of Israel to bring blessings, kindness, and goodness into the world, no matter what situation she

found herself in. And above all, she strove to always be humble before God and to

love and serve others. She signed her note with the simple but powerful words,

“Rabbi Regina Jonas, formerly of Berlin.”

Soon after writing this letter, on October 12, 1944, Regina and her mother were sent on a transport to Auschwitz. There is no record of them in Auschwitz, and it’s believed that Regina and her mother were killed in the gas chambers on the same day they arrived.

To the very end, Rabbi Regina Jonas stayed true to her unwavering commitment to serve God and the Jewish people even in the worst of times.

The Legacy of Rabbi Regina Jonas

For many years, the name of Rabbi Regina Jonas was forgotten. None of her surviving male colleagues, among them Viktor Frankl and Rabbi Leo Baeck, even mentioned her after the war.

Then, in 1991, Katerina von Kellenbach, a professor of Religious Studies, traveled to Berlin to conduct academic research. In the General Archive of German Jews, she discovered a dusty old box filled with papers – papers that belonged to Rabbi Regina Jonas.

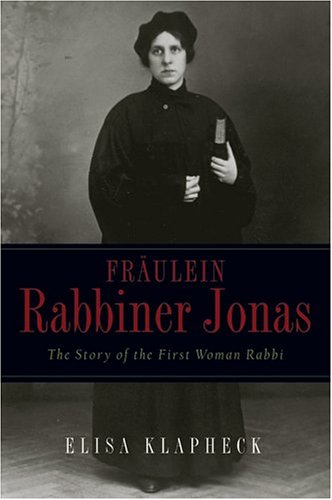

Katerina carefully sorted through the papers and discovered Regina’s thesis, ordination certificate, and a photo of Regina dressed in her rabbinic robes. There were newspaper clippings that profiled Regina and the challenges she faced, and dozens of thank you notes from people she had served.

There was also a note written by a friend of Regina’s, explaining she had entrusted all her precious documents to him on the day she was deported from Terezin. Somehow, these documents had made their way to an archive in Berlin, only to be forgotten there during the years of Communist rule.

Deeply moved and astonished by Regina’s story, Katerina published an article about her in 1994, which circulated widely. Interest in Rabbi Regina Jonas soared, and over the years her story has been told in a biography, a children’s book, and a documentary.

Her memory is also honored and preserved at Yad Vashem, the Jewish Museum in Berlin, and Terezin, where there is a memorial plaque dedicated to her life and legacy. Also at Terezin is a small collection of Regina’s papers, including a list of the lectures she delivered there.

And in recent years, a large group of rabbis designated October 18th as her yahrzeit,

the anniversary of her death. Now, on that day, people all over the world recite the Mourner’s Kaddish in her memory. It’s a fitting and powerful tribute to Rabbi

Regina Jonas, who overcame countless obstacles and dedicated herself to serving

the Jewish community, bringing comfort and hope in the darkest times.